Users can follow a link by clicking on it, which then takes them to the page pointed to. This process can be repeated indefinitely. The idea of having one page point to another, called hypertext, was invented by a visionary M.I.T. professor of electrical engineering, Vannevar Bush, in 1945, long before the Internet was invented.

Pages are viewed with a program called a browser, of which Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator are two popular ones. The browser fetches the page requested, interprets the text and formatting commands on it, and displays the page, properly formatted, on the screen.

Like many Web pages, this one starts with a title, contains some information, and ends with the e-mail address of the page's maintainer. Strings of text that are links to other pages, called hyperlinks, are often highlighted, by underlining, displaying them in a special color, or both.

To follow a link, the user places the mouse cursor on the highlighted area, which causes the cursor to change, and clicks on it. Although nongraphical browsers, such as Lynx, are not as popular as graphical browsers.Voice-based browsers are also being developed.

Users who are curious about the Department of Animal Psychology can learn more about it by clicking on its (underlined) name. The browser then fetches the page to which the name is linked and displays it, as shown in Fig. 5-18(b).

The underlined items here can also be clicked on to fetch other pages, and so on. The new page can be on the same machine as the first one or on a machine halfway around the globe. The user cannot tell.

Page fetching is done by the browser, without any help from the user. If the user ever returns to the main page, the links that have already been followed may be shown with a dotted underline (and possibly a different color) to distinguish them from links that have not been followed.

Note that clicking on the Campus Information line in the main page does nothing. It is not underlined, which means that it is just text and is not linked to another page.

Figure 5-18. (a) A Web page. (b) The page reached by clicking on Department of Animal Psychology.

The basic model of how the Web works is shown in Fig. 5-19. Here the browser is displaying a Web page on the client machine. When the user clicks on a line of text that is linked to a page on the abcd.com server, the browser follows the hyperlink by sending a message to the abcd.com server asking it for the page.

When the page arrives, it is displayed. If this page contains a hyperlink to a page on the xyz.com server that is clicked on, the browser then sends a request to that machine for the page, and so on indefinitely.

Figure 5-19. The parts of the Web model.

The Client Side

An URL has three parts: the name of the protocol (http), the DNS name of the machine where the page is located (www.abcd.com), and (usually) the name of the file containing the page (products.html).

When a user clicks on a hyperlink, the browser carries out a series of steps in order to fetch the page pointed to. Suppose that a user is browsing the Web and finds a link on Internet telephony that points to ITU's home page, which is http://www.itu.org/home/index.html.

Let us trace the steps that occur when this link is selected.

1. The browser determines the URL (by seeing what was selected).

2. The browser asks DNS for the IP address of www.itu.org.

3. DNS replies with 156.106.192.32.

4. The browser makes a TCP connection to port 80 on 156.106.192.32.

5. It then sends over a request asking for file /home/index.html.

6. The www.itu.org server sends the file /home/index.html.

7. The TCP connection is released.

8. The browser displays all the text in /home/index.html.

9. The browser fetches and displays all images in this file.

Many browsers display which step they are currently executing in a status line at the bottom of the screen. In this way, when the performance is poor, the user can see if it is due to DNS not responding, the server not responding, or simply network congestion during page transmission.

To be able to display the new page (or any page), the browser has to understand its format. To allow all browsers to understand all Web pages, Web pages are written in a standardized language called HTML, which describes Web pages.

Although a browser is basically an HTML interpreter, most browsers have numerous buttons and features to make it easier to navigate the Web. Most have a button for going back to the previous page, a button for going forward to the next page, and a button for going straight to the user's own start page.

In addition to having ordinary text (not underlined) and hypertext (underlined), Web pages can also contain icons, line drawings, maps, and photographs. Each of these can (optionally) be linked to another page.

Clicking on one of these elements causes the browser to fetch the linked page and display it on the screen, the same as clicking on text. With images such as photos and maps, which page is fetched next may depend on what part of the image was clicked on.

Rather than making the browsers larger and larger by building in interpreters for a rapidly growing collection of file types, most browsers have chosen a more general solution. When a server returns a page, it also returns some additional information about the page.

This information includes the MIME type of the page (see Fig. 5-12). Pages of type text/html are just displayed directly, as are pages in a few other built-in types. If the MIME type is not one of the built-in ones, the browser consults its table of MIME types to tell it how to display the page. This table associates a MIME type with a viewer.

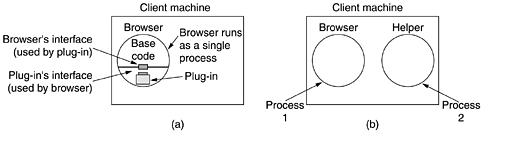

There are two possibilities: plug-ins and helper applications. A plug-in is a code module that the browser fetches from a special directory on the disk and installs as an extension to itself, as illustrated in Fig. 5-20(a).

Because plug-ins run inside the browser, they have access to the current page and can modify its appearance. After the plug-in has done its job, the plug-in is removed from the browser's memory.

Figure 5-20. (a) A browser plug-in. (b) A helper application.

In addition, the browser makes a set of its own procedures available to the plug-in, to provide services to plug-ins. Typical procedures in the browser interface are for allocating and freeing memory, displaying a message on the browser's status line, and querying the browser about parameters.

Before a plug-in can be used, it must be installed. The usual installation procedure is for the user to go to the plug-in's Web site and download an installation file. On Windows, this is typically a self-extracting zip file with extension .exe.

When the zip file is double clicked, a little program attached to the front of the zip file is executed. This program unzips the plug-in and copies it to the browser's plug-in directory. Then it makes the appropriate calls to register the plug-in's MIME type and to associate the plug-in with it.

On UNIX, the installer is often a shell script that handles the copying and registration. Many helper applications use the MIME type application. A considerable number of subtypes have been defined, for example, application/pdf for PDF files and application/msword for Word files.

In this way, a URL can point directly to a PDF or Word file, and when the user clicks on it, Acrobat or Word is automatically started and handed the name of a scratch file containing the content to be displayed.

Helper applications are not restricted to using the application MIME type. Adobe Photoshop uses image/x-photoshop and RealOne Player is capable of handling audio/mp3, for example. On Windows, when a program is installed on the computer, it registers the MIME types it wants to handle.

This mechanism leads to conflict when multiple viewers are available for some subtype, such as video/mpg. What happens is that the last program to register overwrites existing (MIME type, helper application) associations, capturing the type for itself.

As a consequence, installing a new program may change the way a browser handles existing types. Here, too, conflicts can arise since many programs are willing, in fact, eager, to handle, say, .mpg.

During installation, programs intended for professionals often display checkboxes for the MIME types and extensions they are prepared to handle to allow the user to select the appropriate ones and thus not overwrite existing associations by accident.

Programs aimed at the consumer market assume that the user does not have a clue what a MIME type is and simply grab everything they can without regard to what previously installed programs have done.

The ability to extend the browser with a large number of new types is convenient but can also lead to trouble. When Internet Explorer fetches a file with extension exe, it realizes that this file is an executable program and therefore has no helper. The obvious action is to run the program. However, this could be an enormous security hole.

All a malicious Web site has to do is produce a Web page with pictures of, say, movie stars or sports heroes, all of which are linked to a virus. A single click on a picture then causes an unknown and potentially hostile executable program to be fetched and run on the user's machine.

The Server Side

When the user types in a URL or clicks on a line of hypertext, the browser parses the URL and interprets the part between http:// and the next slash as a DNS name to look up. Armed with the IP address of the server, the browser establishes a TCP connection to port 80 on that server.

Then it sends over a command containing the rest of the URL, which is the name of a file on that server. The server then returns the file for the browser to display.

That server, like a real Web server, is given the name of a file to look up and return. In both cases, the steps that the server performs in its main loop are:

1. Accept a TCP connection from a client (a browser).

2. Get the name of the file requested.

3. Get the file (from disk).

4. Return the file to the client.

5. Release the TCP connection.

A problem with this design is that every request requires making a disk access to get the file. The result is that the Web server cannot serve more requests per second than it can make disk accesses.

A high-end SCSI disk has an average access time of around 5 msec, which limits the server to at most 200 requests/sec, less if large files have to be read often. For a major Web site, this figure is too low.

One obvious improvement is to maintain a cache in memory of the n most recently used files. Before going to disk to get a file, the server checks the cache. If the file is there, it can be served directly from memory, thus eliminating the disk access.

Figure 5-21. A multithreaded Web server with a front end and processing modules.

The processing module first checks the cache to see if the file needed is there. If so, it updates the record to include a pointer to the file in the record. If it is not there, the processing module starts a disk operation to read it into the cache.

When the file comes in from the disk, it is put in the cache and also sent back to the client. The advantage of this scheme is that while one or more processing modules are blocked waiting for a disk operation to complete, other modules can be actively working.

Of course, to get any real improvement over the single- threaded model, it is necessary to have multiple disks, so more than one disk can be busy at the same time. With k processing modules and k disks, the throughput can be as much as k times higher than with a single-threaded server and one disk.

1. Resolve the name of the Web page requested.

2. Authenticate the client.

3. Perform access control on the client.

4. Perform access control on the Web page.

5. Check the cache.

6. Fetch the requested page from disk.

7. Determine the MIME type to include in the response.

8. Take care of miscellaneous odds and ends.

9. Return the reply to the client.

10. Make an entry in the server log.

Step 1 is needed because the incoming request may not contain the actual name of the file as a literal string. For example, consider the URL http://www.cs.vu.nl, which has an empty file name. It has to be expanded to some default file name.

Also, modern browsers can specify the user's default language, which makes it possible for the server to select a Web page in that language, if available. In general, name expansion is not quite so trivial as it might at first appear, due to a variety of conventions about file naming.

Step 2 consists of verifying the client's identity. This step is needed for pages that are not available to the general public.

Step 3 checks to see if there are restrictions on whether the request may be satisfied given the client's identity and location.

Step 4 checks to see if there are any access restrictions associated with the page itself. If a certain file (e.g., .htaccess) is present in the directory where the desired page is located, it may restrict access to the file to particular domains, for example, only users from inside the company.

Steps 5 and 6 involve getting the page. Step 6 needs to be able to handle multiple disk reads at the same time.

Step 4 checks to see if there are any access restrictions associated with the page itself. If a certain file (e.g., .htaccess) is present in the directory where the desired page is located, it may restrict access to the file to particular domains, for example, only users from inside the company.

Steps 5 and 6 involve getting the page. Step 6 needs to be able to handle multiple disk reads at the same time.

Step 7 is about determining the MIME type from the file extension, first few words of the file, a configuration file, and possibly other sources.

Step 8 is for a variety of miscellaneous tasks, such as building a user profile or gathering certain statistics.

Step 8 is for a variety of miscellaneous tasks, such as building a user profile or gathering certain statistics.

Step 9 is where the result is sent back and step 10 makes an entry in the system log for administrative purposes.

If too many requests come in each second, the CPU will not be able to handle the processing load, no matter how many disks are used in parallel. The solution is to add more nodes, possibly with replicated disks to avoid having the disks become the next bottleneck. This leads to the server farm model of Fig. 5-22.

A front end still accepts incoming requests but sprays them over multiple CPUs rather than multiple threads to reduce the load on each computer. The individual machines may themselves be multithreaded and pipelined as before.

Figure 5-22. A server farm.

If too many requests come in each second, the CPU will not be able to handle the processing load, no matter how many disks are used in parallel. The solution is to add more nodes, possibly with replicated disks to avoid having the disks become the next bottleneck. This leads to the server farm model of Fig. 5-22.

A front end still accepts incoming requests but sprays them over multiple CPUs rather than multiple threads to reduce the load on each computer. The individual machines may themselves be multithreaded and pipelined as before.

Figure 5-22. A server farm.

One problem here is that there is no longer a shared cache because each processing node has its own memory-unless an expensive shared-memory multiprocessor is used.

One way to counter this performance loss is to have a front end keep track of where it sends each request and send subsequent requests for the same page to the same node. Doing this makes each node a specialist in certain pages so that cache space is not wasted.

Figure 5-23. (a) Normal request-reply message sequence. (b) Sequence when TCP handoff is used.

Figure 5-23. (a) Normal request-reply message sequence. (b) Sequence when TCP handoff is used.

URLs—Uniform Resource Locators

When the Web was first created, it was immediately apparent that having one page point to another Web page required mechanisms for naming and locating pages. In particular, three questions had to be answered before a selected page could be displayed:

1. What is the page called?

2. Where is the page located?

3. How can the page be accessed?

If every page were somehow assigned a unique name, there would not be any ambiguity in identifying pages. Nevertheless, the problem would not be solved. Consider a parallel between people and pages.

In the United States, almost everyone has a social security number, which is a unique identifier, as no two people are supposed to have the same one. Nevertheless, if you are armed only with a social security number, there is no way to find the owner's address.

The Web has basically the same problems. The solution chosen identifies pages in a way that solves all three problems at once. Each page is assigned a URL (Uniform Resource Locator) that effectively serves as the page's worldwide name.

URLs have three parts: the protocol (also known as the scheme), the DNS name of the machine on which the page is located, and a local name uniquely indicating the specific page (usually just a file name on the machine where it resides).

As an example example, the Web site for the author's department contains several videos about the university and the city of Amsterdam.

In the United States, almost everyone has a social security number, which is a unique identifier, as no two people are supposed to have the same one. Nevertheless, if you are armed only with a social security number, there is no way to find the owner's address.

The Web has basically the same problems. The solution chosen identifies pages in a way that solves all three problems at once. Each page is assigned a URL (Uniform Resource Locator) that effectively serves as the page's worldwide name.

URLs have three parts: the protocol (also known as the scheme), the DNS name of the machine on which the page is located, and a local name uniquely indicating the specific page (usually just a file name on the machine where it resides).

As an example example, the Web site for the author's department contains several videos about the university and the city of Amsterdam.